Oh, Cars.

Right up front in this review, I should say: I love Cars. And I recognize that this is not a popular opinion.

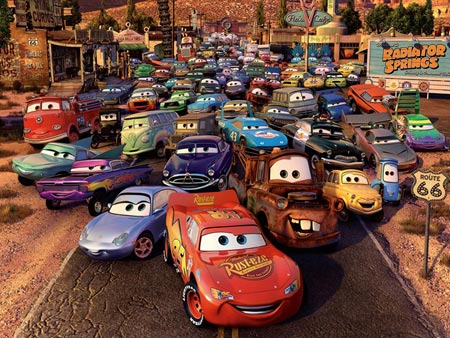

A Doc-Hollywood-meets-NASCAR mashup in a world populated by anthropomorphic automobiles, Cars tells the story of a hotshot rookie racecar who gets arrested in a small town off the now defunct Route 66, and is forced to do community service when he should be out courting his dream of fame and fortune as the winner of the Piston Cup. Inevitably, he meets a beautiful girl—er, Porsche—, befriends a tow truck, discovers a missing racing legend, and learns the secret of living a happy life just in time to be rushed to his big race, where we see that he has become a much better racecar while learning humility and gratitude along the way.

Cars was the first film Pixar made that didn’t score absolutely stellar reviews, and that still draws a lot of criticism from fans of the studio. My experience is that the film, while carrying a few dedicated fans like myself, generally seems to provoke reactions among my peers ranging from “ehhhh,” to hatred. Here are three reasons I think this film doesn’t resonate well with them:

The world is flimsy.

So much of the wonder of Pixar films is in creating a window into a world that we can just see if only we turn our heads sideways and possibly hop on one leg. Our toys come to life while we’re out of the room. There really are monsters in our closets. Superheroes secretly live among us. The world of Cars, on the other hand, bears absolutely no scrutiny. How do cars grow up? Why do they have to sleep? How do they mate? How do they manage to build their own highways without opposable thumbs? I have no idea.

The subject is unappealing.

I could probably write a thousand words just on the cultural implications of scorning a movie based on NASCAR, but suffice it to say that the sport doesn’t carry a lot of popularity amongst my 20-and-30-something New York City movie nerd friends. I’m neutral on NASCAR personally, but we can’t pretend it isn’t a popular sport. The NASCAR fan base is second only to the NFL in American sports, and, despite the political rhetoric built up around the “NASCAR dad” demographic, the sport draws a fairly diverse crowd.

The nostalgia isn’t aimed at us.

A lot of the gut-punch nostalgia of Pixar films is aimed at people my age, who are no longer children but remember vividly what it was like to be a child. The nostalgia of Cars, however, aims a generation older than us, tied into sentimentality around Route 66, backcountry roads and an invitation to go for a lazy drive just for the fun of it, in a world where oil prices haven’t skyrocketed and that type of imagery is still personal.

And here three reasons why, despite what I’ve said above, I still really love this film:

It’s gorgeous and cleverly animated.

Cars really shows off Pixar’s ability to fill an enormous screen with pixel-perfect colors and images. The landscape of the film alone makes it worthy of our appreciation. But on top of that, I think the animation of Cars solves a number of technical challenges brilliantly—for example, how do you create an entire action-packed film about characters who don’t have hands?

It is full of charming, well-articulated characters, like any Pixar film.

Pixar does fantastic character work, and this shines through in Cars. Even the tiniest bit parts give an impression of an entire life off screen. They range from the easy charm of Mr. The King, the racing legend with a worrying wife and aspiring teenage son, to the mama-bear-type Flo, the Motorama show car keeping everybody topped off. There are too many great character moments in Cars to list them all, but I particularly love the cameo of the Car Talk hosts, Guido’s pit stop (maybe Guido has figured out the secret of opposable thumbs?) and the laugh-out-loud hilarity of Mack’s movie reviews, as voiced by the suddenly self-aware John Ratzenberger.

It tells a compelling story.

One of the common critiques of Cars is that it’s too long, but I find that it works; the density of the characters in combination with the beautiful animation invites you to give it the space it needs to tell several smaller stories within the main arc. It’s also critiqued as predictable. Now, let me be honest; I have a very high tolerance for predictable storylines. Bring me a fairy tale with a happy ending any day of the week. We all know exactly how Cars is going to end the minute it begins, but the film still does a very good job of surprising us along the way, and gives us a great ending sequence in which we’re still on the edge of our seats to find out who wins the race.

So why do we get so mad about Cars? I speculate that this movie is maligned by many of my peers because it is squarely placed within demographics we do not share. If you are mad that Pixar made this film, please consider this: you are mad at a children’s film company for making a movie aimed at children. Cars is beloved by children.

How can we tell? Merchandising. Cars may not have scored the soaring reviews we’ve come to expect from Pixar, but in the 5 years following its release, Pixar made 10 billion dollars in merchandising revenue off of the film. To put this in context: the Cars merchandising revenue stream is equivalent to that of Star Wars, Spider-man and Harry Potter.

This, incidentally, also sheds light on the “dreaded” sequel, Cars 2. (Full disclosure: haven’t seen it.) To not make a sequel based on such a successful franchise would be a very poor financial move on Pixar’s part. I’m not in full support of making sequels to films just to flog out additional advertising revenue, but if you’re looking for a reason why the Pixar reputation is supposedly besmirched by such a poor story extension, there it is. It’s because kids loved it, and it made them a lot of money.

But then again, I’ve read comments and interviews to suggest that Cars is John Lasseter’s baby, and that he loved making the films just as much as little kids love watching them. And I like that version of the story better; a director makes a fun, profitable, creative film, and keeps it going, despite a few mixed reviews, because it’s just so dear to his heart.

In my opinion, Cars suffers not because it is a bad film, but because it is a good film in the company of great ones. Cars suffers because it was made 10 years into Pixar’s string of breakout, blockbuster successes, and at that point we expect more from the studio than a solidly built storyline with charming bit characters and gorgeous animation. You’ve done that, Pixar. We know.

But I certainly don’t feel that impatience when I watch the film, and I have a whole lot of kids to back me up—and maybe some adults too. Watching Cars again for this review meant spending a lot of time saying, “wow,” and “awwwww,” and “yay!” at my screen. It made me laugh, and it made me happy. In the end, that’s what Pixar does best.

Sara Eileen Hames tells stories, organizes people, and runs a magazine. Sometimes she works in start-up consulting, sometimes she works as a writer, and sometimes (rarely) she doesn’t work at all.